On November 14th of this year, the FDA cleared the path for Upside Foods to sell its cell-culture-based chicken products within the US. This is the first product of its kind to be cleared for commercial sale within the Americas, with only Singapore having previously cleared a similar product for sale, back in December of 2020. This latter product comes courtesy of another California start-up called Eat Just.

Since that initial approval in Singapore, Eat Just has begun to set up a 2,800 square meter (~30,000 square feet) production facility in Singapore that is scheduled to begin producing thousands of kilograms of slaughter-free meat starting in the first quarter of 2023. This would make it the top-runner in the cultured meat industry, which to this point has seen dozens of start-ups, but precious few actual products for sale.

With CEO Josh Tetrick of Eat Just projecting price equality between their cultured meat and meat from animals by 2030, could the FDA’s approval herald the dawn of slaughter-free meat? There are obviously still hurdles, but as we’ll see, the idea is not nearly as far-fetched as one might think.

A Long History

The history behind cell cultures stretches back to the 19th century, when through experimentation it was discovered that tissues and entire organs could be kept alive, even after having been separated from the body. Subsequent research during the early 20th century increased our understanding of tissue and cell cultures, which during the 1940s and 1950s led to such medical leaps forward as growing viruses in cell cultures for the sake of producing vaccines.

The injectable polio vaccine, developed by Jonas Salk, was among the first products that was mass-produced courtesy of such cell cultures. Beyond vaccine development, the ability to not only isolate cells, but to keep them alive for extended periods of time has led to countless medical and scientific breakthroughs over the intervening decades. Some of these cell cultures as used in laboratory settings are also immortal, either because of their starting point as a (human) cancer cell, due to them being stem cells, or because of immortalization treatment. Having immortalized cell lines allows for long-term studies on a well-documented type of cell.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such cell cultures are involved in the initial step of setting up a cultivated meat production line. In the FDA Memorandum covering the approval of Upside Food’s product the following steps are detailed:

- Cell isolation

- Establishment of cell lines

- Establishment of Master Cell Banks (MCB)

- Proliferation phase

- Differentiation phase

- Harvest of cell material

None of these steps are necessarily new or uncommon within a laboratory setting. The isolation of the initial seed cells involves extracting these from a chicken. These then have to be characterized and checked for any pathogens. The resulting cells are then immortalized using gene-therapy with telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) as needed, to establish the master cell lines. These cell lines are immortal and can thus be used for the further duration of the production line.

During the proliferation phase, some of the cells from the cell banks are introduced to a bioreactor, where the cells are encouraged to multiply in suspension culture, while bathed in all the nutrients they need, and with a constant pH and temperature being maintained. Once enough cell material has formed, they are moved to the next phase, which is where these cells will differentiate into both the muscle (myocyte) and connective (fibrocyte) tissues. Both will adhere to the bioreactor’s walls, and to each other, forming a multi-cellular tissue.

After this phase, the contents of this final bioreactor can be extracted and is essentially ready for preparation and consumption.

Growing Pains

As the saying goes, if something was easy, someone else would already have done it a long time ago. In the case of cultured meat most of the challenges lie in scaling up from a laboratory setting involving small batches of cell culture, to massive bioreactors capable of outputting thousands upon thousands kilograms of product.

Making sure that these bioreactors manage to keep the cells content as nutrients are added and waste products removed is one thing, but another is the entire supply chain surrounding the operation. At this point in time, there is no massive industry capable of delivering these nutrients on a scale required to replace a significant part of today’s meat consumption. All of these supply lines will have to grow along with this nascent cultured meat industry.

A major bottleneck and cost factor here is the growth medium, especially the growth factors that the cells require in order to multiply. Common sources for laboratories include fetal bovine serum (FBS) along with the serum from other animals. Generally slaughterhouses are the primary source of the blood from which the serum is extracted. Finding replacements for this serum and their growth factors is an ongoing topic, and one that is obviously highly relevant for cultured meat.

One alternative is made from human blood, called hPL (human platelet lysate). This is a substitute for FBS that is created from previously extracted platelets that have since expired. Since these were extracted from donated blood for transfusion purposes, hPL forms a cruelty-free alternative source. The main obstacles here are that the amount is only enough for small-scale laboratory settings, and there are issues with cost and consistency across batches.

An ideal alternative for FBS, hPL and similar would be a fully artificial, synthesized alternative, as this would alleviate any ethical and food safety concerns. Unfortunately, as also covered in a 2021 review by Chelladurai et al. in Heliyon, a clear alternative does not exist yet. This reinforces the notion that finding a serum-free replacement for cultured meat is likely to form one of the major obstacles in the near future, both in terms of its ethical image and the sense of its ultimate price tag.

Still Worth It

Even with the clear challenges in scaling up cultivated meat products, there is no denial that its potential positive impacts can be massive. In a 2017 report (PDF) by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), it is noted that agriculture is responsible for about 70% of global freshwater usage, a significant amount of which goes into feeding cattle — 15 ton of water per kilogram of meat — and other animals intended for meat production.

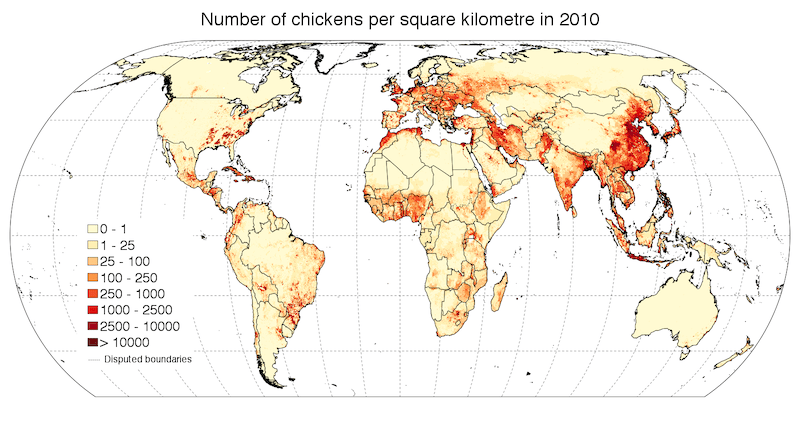

When there are approximately three chickens on this Earth for every single human (~24B chickens), with similar numbers for cattle and sheep, it’s not hard to see how the meat industry has somewhat of an impact on the environment, and correspondingly the climate. If we can over the coming decades remove the need for animals to be grown for the slaughterhouse, we stand to regain many thousands of square kilometers of pasture and farm land, with corresponding cuts in greenhouse gases.

By moving the entire meat industry into fully controlled, sterile factories, this would also essentially eliminate issues with contamination, such as salmonella in chicken meat. It’d alleviate the need for antibiotics and generally result in a safer, more predictable and consistent product, while still being the same meat. Just without the part where an animal is raised from a chick, calf or piglet before its demise in an abattoir.

Opinions Remain Divided

It should bear little repetition that not everyone agrees on the need for cultured meat, with alternatives based on plant proteins generally wheeled out as the obvious alternative to meat. Even though I’m a long-time vegetarian, the notion that not everyone will want to give up eating meat seems unavoidable. However, since the main issues with the meat industry are the aforementioned environmental impact, cultured meat would seem to be a more than acceptable solution there.

Assuming we can make cultured meat work by 2030, we may see a corresponding plunge in feed required for livestock, alleviating the pressure to produce enough food for an ever-growing human population, while still allowing those who can’t give up their meat habit to dig into a fresh chunk of genuine chicken or beef. All thanks to some scientists who tinkered with some animal tissues over a hundred years ago.